Evaluating the Prognostic Efficacy of Scoring Systems in Neurocritical and Neurosurgical Care: An Insight into APACHE II, SOFA, and GCS

Article information

Abstract

Background

To investigate the utility of established prognostic scoring systems, such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), for patients admitted to a neurosurgical intensive care unit (ICU).

Methods

Among neurosurgical patients admitted to the neurosurgical ICU in a tertiary hospital from January 2015 and December 2022, only patients who had an ICU stay exceeding three days were included. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality.

Results

In this study, a total of 3,417 patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 3,052 (89.3%) survived until hospital discharge. Both the APACHE II and SOFA scores were significantly higher in non-survivors than in survivors (p<0.001 for both). Conversely, GCS and GCS motor score (GCS M) were substantially lower in non-survivors (p<0.001). Among the commonly used scoring systems, the APACHE II score emerged as the most effective predictor of in-hospital mortality (C-statistic of 0.887, 95% confidence interval: 0.869–0.887). Remarkably, the GCS M proved to be equally effective as the SOFA score in predicting in-hospital mortality (p=0.435) and offered the additional advantage of being simpler to use.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that these scoring systems offer valuable insights into the clinical prognosis of patients in the neurosurgical ICU. Moreover, the GCS M stands out as a feasible and reliable metric for predicting in-hospital mortality among neurosurgical ICU patients.

INTRODUCTION

The prognosis of critically ill patients remains an intricate yet crucial component in the management and decision-making processes within intensive care units (ICU)1,2). Several scoring systems like the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) are often utilized to gauge the severity of a patient's condition and to predict clinical outcomes3-5). While these scores have proven valuable in general ICUs, they are not without limitations—especially when applied to specialized areas like neurointensive care.

The landscape of neurointensive care presents unique challenges and complexities, often demanding a specialized approach to both management and prognosis6). Neurocritically ill patients often suffer from a wide array of neurological injuries and diseases, ranging from traumatic brain injuries to strokes, each with distinct pathophysiologies and prognostic indicators7,8). Despite the growing body of research in critical care medicine, there is currently a paucity of scoring systems that are specifically tailored for predicting outcomes in neurointensive care settings. In addition, there is a limited body of research investigating the efficacy of established scoring systems like APACHE II score, SOFA score, and GCS in predicting outcomes specifically for patients in neurointensive care settings. Generally, these prognostic scoring systems have been commonly used for predicting clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the utility of established prognostic scoring systems, such as the APACHE II score, SOFA score, and GCS, for patients admitted to a neurosurgical ICU.

METHODS

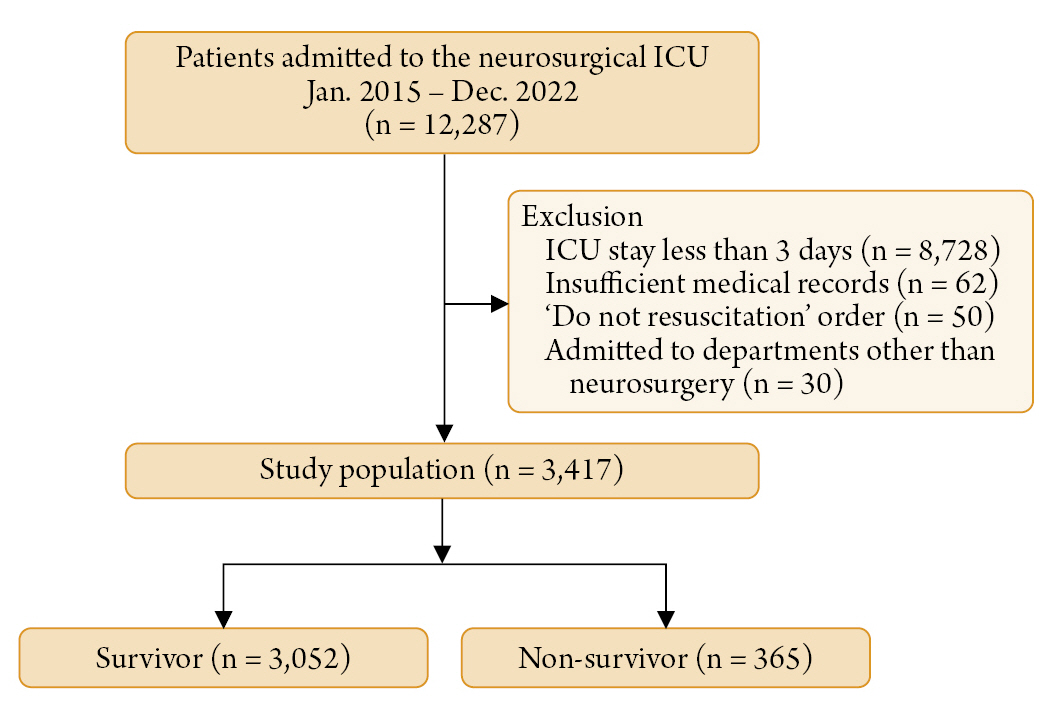

This was a retrospective, single-center, observational study conducted on patients admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit (ICU) of a tertiary referral hospital (Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea) between January 2015 and December 2022. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (No. SMC 2020-09-082) and was carried out in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design of the study, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent. Our study population consisted of patients who had been admitted to the Neurosurgical ICU for the management of neurocritical illnesses or for postoperative care following neurosurgical procedures. Furthermore, only patients who had an ICU stay exceeding three days were included. We excluded patients with incomplete medical records, those with 'Do Not Resuscitate' orders, those admitted to departments other than Neurosurgery, or those transferred to other facilities with unknown prognoses (Fig. 1).

Definitions and endpoints

In this study, we retrospectively collected baseline characteristics including comorbidities, behavioral risk factors, ICU management strategies, and laboratory data through our Clinical Data Warehouse, known as "Darwin-C." This platform was specifically designed to enable researchers to search and retrieve de-identified medical records from electronic archives. In this study, results of blood laboratory tests as well as APACHE II score, SOFA score, and GCS were automatically extracted from the medical records. The APACHE II score was calculated based on initial values from 12 routine physiological measurements, age, and pre-existing health conditions to provide a comprehensive measure of disease severity9). An increasing score, ranging from 0 to 71, was strongly correlated with the risk of subsequent in-hospital mortality9). The SOFA score was determined by evaluating individual components related to respiratory, coagulation, liver, cardiovascular, central nervous system, and renal functions, as described in a prior study10). Both the APACHE II and SOFA scores were computed using the worst values recorded during the initial 24 hours following ICU admission. For intubated patients, the verbal component of the GCS was estimated using eye and motor scores, in accordance with previously established methods11). Invasive intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring was performed by neurosurgeons. The decision to initiate ICP monitoring was primarily based on brain imaging findings and the patient’s clinical condition. Specifically, the presence of space-occupying lesions, such as brain tumors, abscesses, and intracranial hemorrhages (including epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, and intraparenchymal hematoma), warranted monitoring when increased ICP was suspected. In cases presenting with cerebrospinal fluid flow obstruction due to hydrocephalus, an external ventricular drain was predominantly used. Furthermore, in instances of cerebral edema or when clinically suspected increased ICP was evident, invasive ICP monitoring was employed, contingent on the neurosurgeon's assessment, to facilitate neuromonitoring. The primary endpoint of this investigation was in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables are shown as counts and corresponding percentages. Statistical comparisons were made using Student's t-test for continuous variables and either the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical ones. The predictive performance of each scoring system was assessed through the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with sensitivity plotted against 1-specificity. The areas under the curves (AUCs) were compared using DeLong et al.'s nonparametric approach for evaluating two correlated AUCs12). Clinically relevant variables—such as severity scoring systems, age, sex, comorbidities, behavioral risk factors, reasons for ICU admission, and ICU management practices—were subjected to multiple logistic regression analysis to identify statistically significant predictors. The adequacy of the prediction model was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, as well as the AUCs. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted using R Statistical Software (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics and clinical outcome

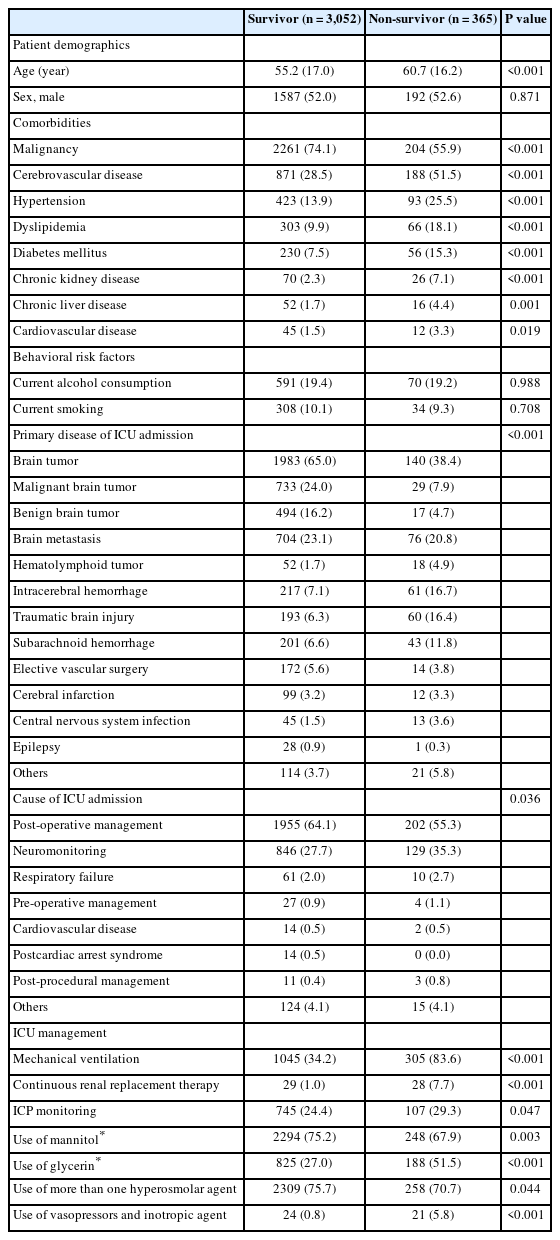

A total of 3,417 patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 3,052 (89.3%) survived until hospital discharge. The median age of the patients was 55.7 ± 17.0 years, and 1,779 (52.1%) were male. The most prevalent comorbidities among the study population were malignancy (72.1%) and cerebrovascular disease (31.0%). The leading cause of ICU admission was brain tumor, accounting for 62.1% of cases. Among patients with brain tumors, the most common reasons for ICU admission were post-operative care (39.5%) and neuromonitoring (17.2%). Interventions such as mechanical ventilation, intracranial pressure monitoring, the use of multiple hyperosmolar agents, and vasopressor and inotropic agent administration were more frequently observed in non-survivors. A comparative analysis of the baseline characteristics between survivors and non-survivors is presented in Table 1.

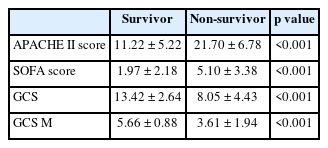

Relationship between APACHE II, SOFA, and GCS

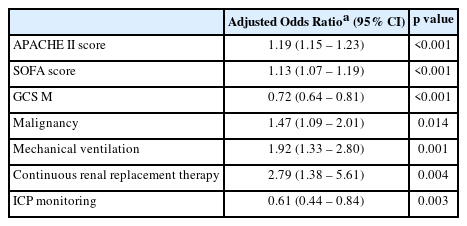

A comparison of severity scoring systems between survivors and non-survivors is presented in Table 2. Both the APACHE II and SOFA scores were significantly higher in non-survivors than in survivors (p<0.001 for both). Conversely, GCS and GCS M were substantially lower in non-survivors (p<0.001). Multivariable analysis revealed that the APACHE II score (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.19, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–1.23), SOFA score (adjusted OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.07–1.19), and GCS M (adjusted OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.64–0.81) were significant predictors of in-hospital mortality. Other variables, including malignancy (adjusted OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.09–2.01), mechanical ventilation (adjusted OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.33–2.80), continuous renal replacement therapy (adjusted OR: 2.79, 95% CI: 1.38–5.61), and ICP monitoring (adjusted OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.44–0.84) were also significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. The model demonstrated good fit with a Hosmer–Lemeshow Chi-squared value of 6.135 (df=8, p=0.632) and an AUC of 0.906 (95% CI 0.890–0.923) (Table 3).

Predicting factors for in-hospital mortality in neurocritically ill patients and neurosurgical patients assessed using logistic regression model

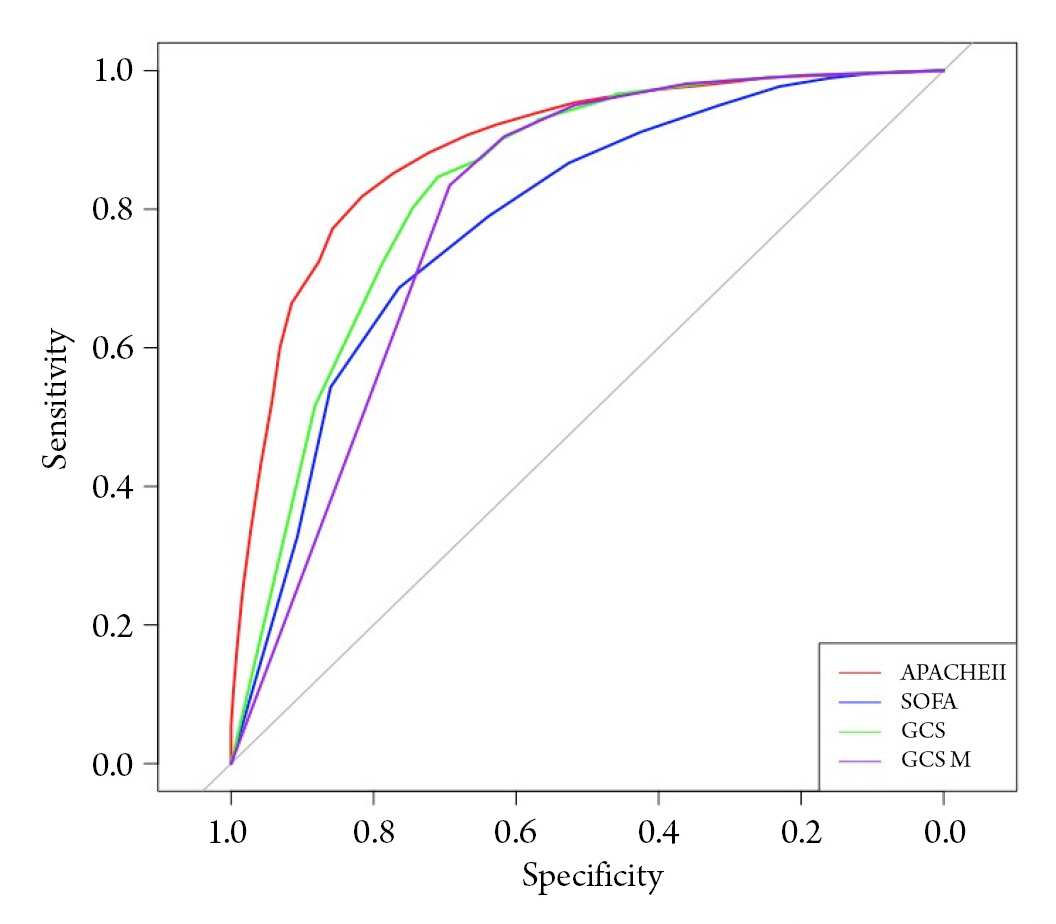

In the ROC curve analysis for predicting in-hospital mortality, the APACHE II score demonstrated superior performance with a C-statistic of 0.887 (95% CI: 0.869–0.887), which was greater than that of the SOFA score (C-statistic: 0.783, 95% CI: 0.757–0.783), GCS (C-statistic: 0.833, 95% CI: 0.808–0.833), and GCS M (C-statistic: 0.796, 95% CI: 0.769–0.796) (all p<0.01). Moreover, the AUC for GCS was greater than those for the SOFA score and GCS M (both p<0.01). However, there was no significant difference in predictive performance between the SOFA score and GCS M (p=0.435) (Fig. 2).

Receiver operating characteristic curves for prediction of in-hospital mortality using Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and motor score of GCS (GCS M). AUC: areas under the curve, CI: confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the utility of widely recognized prognostic scoring systems—namely, the APACHE II score, SOFA score, and GCS—in neurocritically ill and neurosurgical patients. Our major findings can be summarized as follows: First, statistically significant differences were observed in the APACHE II, SOFA, GCS, and GCS M scores between survivors and non-survivors. Second, multivariable analysis identified several variables, including APACHE II score, SOFA score, GCS M, malignancy, mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy, and ICP monitoring, as significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. Among the commonly used scoring systems, the APACHE II score emerged as the most effective predictor of in-hospital mortality. Remarkably, the GCS M proved to be equally effective as the SOFA score in predicting in-hospital mortality and offered the additional advantage of being simpler to use. In conclusion, all the evaluated scoring systems, including the APACHE II score, SOFA score, GCS, and GCS M, demonstrated utility in predicting clinical outcomes in patients admitted to a neurosurgical ICU.

In the complex and dynamic environment of the ICU, the utilization of validated scoring systems like the APACHE II and the SOFA score becomes imperative for several reasons. These scoring systems provide healthcare providers with a structured, evidence-based framework to assess the severity of illness, enabling timely and appropriate medical interventions13). By offering a quantitative measure of disease severity, these scores help in stratifying patients based on risk, thereby aiding in the allocation of vital resources and guiding clinical decision-making14,15). Additionally, they facilitate more transparent and data-driven discussions with family members about the potential prognosis and assist in cost-benefit analyses14,15). Importantly, they can also serve as valuable research tools, providing a standardized measure of patient severity that allows for meaningful comparisons across studies and settings. Despite their limitations and the need for periodic updates and revisions, the centrality of such scoring systems in optimizing patient outcomes in the ICU cannot be overstated. Generally, prognostic scoring systems are invaluable for assessing disease severity, conducting cost-benefit analyses, and informing clinical decision-making3,5). However, many of these systems are complicated and challenging to implement, particularly in critically ill patients16). Given these limitations, there is a need for simplified yet reliable scoring systems. In this context, the GCS M score emerges as a feasible and reliable metric for predicting in-hospital mortality among neurocritically ill and neurosurgical patients17).

The APACHE II score may have advantages over other commonly used indices like the SOFA score or the GCS in certain contexts9). APACHE II not only incorporates a wide range of physiological variables but also considers age and pre-existing comorbidities, thus providing a comprehensive overview of a patient's condition4). This multidimensional approach potentially allows for a more nuanced risk stratification of ICU patients, which can be crucial for tailoring treatment strategies and resource allocation. Additionally, APACHE II's more extensive set of criteria might offer higher predictive validity for a broader spectrum of diseases and complications, making it a more versatile tool in diverse clinical settings18). While all of these scoring systems serve the essential function of aiding prognosis and guiding treatment, the unique features of APACHE II may render it particularly effective in capturing the complex interplay of factors that determine outcomes in critically ill patients. Therefore, in this study, the APACHE II score demonstrated greater predictive accuracy for clinical prognosis of patients in the neurosurgical ICU19).

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective review of medical records and data extracted from the Clinical Data Warehouse. The nonrandomized nature of registry data might have resulted in a selection bias. Second, in measuring the GCS, we estimated the verbal score for intubated patients based on their eye and motor scores, following the methodology used in previous studies11). However, it should be acknowledged that this approach may not be entirely flawless. Third, in our study, unlike other ICU research, there was a disproportionately high prevalence of patients with malignancy and brain tumors. Although the present study provides valuable insights, prospective large-scale studies are needed to further confirm the usefulness of severity scoring systems in predicting clinical outcomes of neurocritically ill patients with evidence-based conclusions.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored the utility of well-established prognostic scoring systems, including the APACHE II score, SOFA score, and GCS, for assessing outcomes in neurocritically ill and neurosurgical patients. Our findings indicate that these scoring systems offer valuable insights into the clinical prognosis of patients in the neurosurgical ICU. Moreover, the GCS M stands out as a feasible and reliable metric for predicting in-hospital mortality among this patient population.

Notes

Ethics statement

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (No. SMC 2020-09-082) and was carried out in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design of the study, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JAR. Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing: SC, JAR. Formal analysis, Statistical analysis: SC, HK.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Regarding data availability, our data are available on the Harvard Dataverse Network (http://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZSFPUY) as recommended.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Suk Kyung Choo, the nursing director of the neurosurgical intensive care unit, for her valuable advice and insightful discussions. Additionally, we extend our thanks to all the nurses in the neurosurgical intensive care unit at Samsung Medical Center for their exceptional work.